I had carpel tunnel surgery on my right hand 10 days ago. All went well. Next month, I’ll have it again on the left hand. I cherish my hands and what they can do, so I’ll do what I can to keep them in working order. This upcoming surgery reminded me of an essay/chapter I wrote for a book I was working on back in 2016. I’m uncertain as to whether I’ll return to writing the book, so I wanted to share it with you today. Here goes…

With a silent snap, I lost a lifeline. It was June 8, 2002, and the end of a long weekend of teaching at an art retreat in Madison, Wisconsin. Some of the teachers and students wanted to prolong the artmakers high, so after class, a group of us piled into a van and headed for Florilegium, the luscious eye candy of a shop nearby that was reported to have velvet flowers, beads, buttons, fibers, cool tools and more - just the kind of trouble we were looking to get into. We headed back into the van an hour later, loot in tow (mine to the scary sweet tune of $119). I had called shotgun, so after everyone piled in the back, I cavalierly swung my left index finger into the rear sliding door and gave it a firm tug. Never having owned or driven a van, I thought they all closed with a tug of the door. This one did not. It had the new-to-me safety feature that locked the door in place until the driver pushed a button to activate the close.

At that moment of tug, I felt a definite sensation inside my finger, as if a rubber band, stretched beyond capacity, had just snapped. There wasn’t any pain, just weakness, a little limp, lifeless almost. I knew it wasn’t broken, maybe sprained? strained? Not wanting to dampen the mood or cause alarm, I didn’t say anything to anyone. As mothers are prone to do, I figured I’d use the wait-and-see approach and re-evaluate tomorrow. The next day, babying the finger, I packed up without pain and headed to the airport, still thinking it was one hell of a strain, as if I had overworked the poor thing and the muscles had nothing left to give.

I boarded, settled into my seat, and reached up to push the reading light button. I began a quiet panic. There was no strength in my finger. I couldn’t straighten it. It was as limp as a wet noodle. It wouldn’t respond to any intention on my part. This lifeline I took for granted had been cut. Fear set in, working its way up my body, first that sick feeling you get inside your stomach, followed by the quickening heartbeats. Beads of sweat rose on my forehead, and worry chatter took control of my thoughts. “What if I lose the use of this finger? Will I still be able to make art? How could I have been so stupid, so careless?” The two-hour, Madison to DC flight felt like an eternity. I wouldn’t be landing until after the doctor’s office closed and yet I didn’t think it was an emergency room situation. I knew this was something I would only entrust to a hand surgeon.

Did you know that tendons are just like rubber bands, connecting muscle to bone, stretching, and contracting to enable us to perform a myriad of specialized and everyday tasks? I learned of their importance and fragility the next day when the doctor determined I had torn the extensor tendon right off the bone. Immediate surgery was necessary while the tear was still fresh. The scar is now barely visible, but the domed bone screw inserted just to the right of the knuckle, reattaching the tendon to the bone, is quite noticeable. A lasting reminder. I endured the after-pain of surgery and bulky bandages, an awkward hand splint for a month, weeks of physical therapy (re)learning how to pick up a penny and squeeze a ball, and all the while singlehandedly performing daily tasks and simple, everyday actions with my right hand. It took me a whole year to regain the delicate, fine motor control needed to pick up things like a straight pin, a piece of lint, or a stray thread. I learned a new appreciation for infants' process, learning how to grasp and master picking up a Cherrio. The experience taught me one very important lesson. Never, never, ever take your hands for granted.

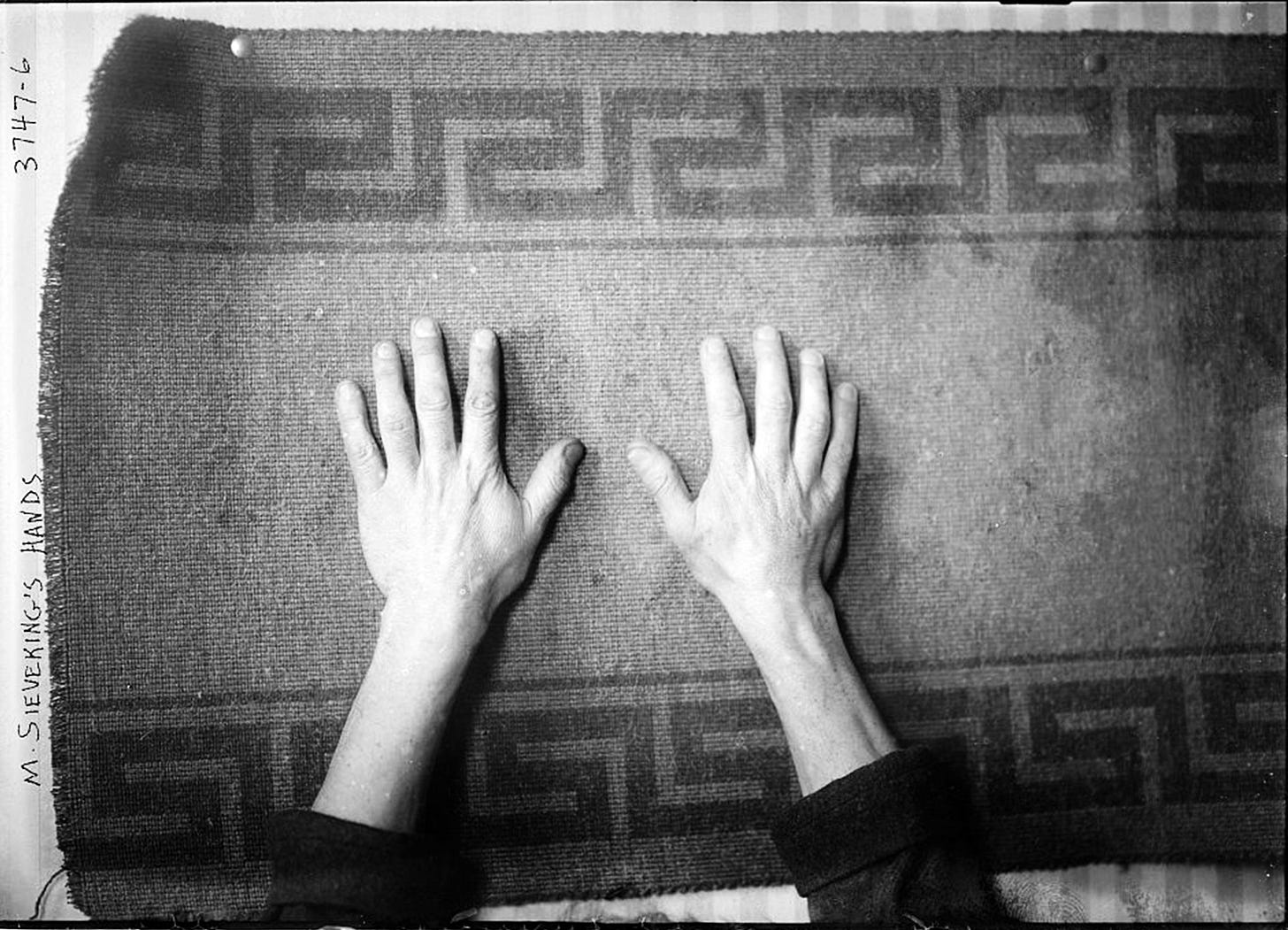

I am fascinated with hands. I’ll catch a glimpse of my hand and stop to stare and admire it in various poses, like the scientific marvel and work of art that it is, awed by its own particular, and sometimes peculiar, beauty. I have a board full of hands on Pinterest. My studio is adorned with a ceramic glove mold (size 8), a small carved wooden hand, and two wooden replica Santos with open outstretched hands. I am not the only one enamored with Alfred Stieglitz’s photographs of Georgia O’Keefe’s hands, some of the most sensuous photographs you will ever see. But it’s not always about beauty. A friend once said, “I've never been told I have beautiful hands, but I treasure the comment a boyfriend once made that my hands looked like they could and did make things. Practical hands, to me, are a bigger compliment than pretty hands.” I so agree. Our hands were made for making, and that is what makes them beautiful, exquisite even.

16th-century philosopher René Descartes called the hand our outer brain. Aristotle considered the hand to be the “instrument of instruments.” To psycholinguist David McNeill, they are “windows into our thought process.” The open right hand is used as a sign of greeting, friendship, and protection in many societies throughout history. Hands are used to communicate and to gesture, both intentionally and unintentionally. We raise our hand to be heard, to ask a question, to signal hello, and wave goodbye. Our hands become speech for the deaf through sign language and eyes for the blind through touch. Hands heal, whether it is from the scalpel in a surgeon’s hand, the laying on of hands, the flow through the hands of the energy healer, or the placing of our hand upon another to soothe their fears and tears. Hands create. I consider them an extension of our soul. The world is at your fingertips with all its potential and possibilities.

As a science nerd, I find it amazing how the cerebral cortex, the part of our brain that makes us human, the brain's outer, convoluted grey matter, controls these magical tools. The size of each area of the cerebral cortex is proportional to the required accuracy necessary to control both sensory and motor functions throughout the body. The two largest areas are devoted to the hands and the mouth. One whole quarter of your entire cerebral cortex is dedicated to the use of your hands. With so much gray matter given over to your hands, they obviously play a significant role in who you are and how you function, both physically and spiritually. As a bonus, active and regular use of your hands in meaningful and purposeful activities keeps this large portion of your brain active and healthy.

We were designed to make use of our hands. And we do. Constantly, and without much, or any, thought. We perform everyday tasks all day - texting, turning doorknobs, tearing open a package, pointing, playing, patting, wiping a tear. We take our hands for granted and do not realize the exquisite potential they hold. (Unless you lose the use of one.) Your hands are exceptional divine tools designed for creating.

Creative use of your hands connects you to your soul. It is through your hands that you make your soul visible. Your hands are the bridge between the outer world and your inner soul. Writer May Sarton says, “It is only when we believe that we are creating the soul that life has any meaning.” You create your soul when you use your hands - hands that make meaning, make memories, and make your mark in and on the world. Your hands are vehicles that enable you to find solace in the stitching, peace in the preparation, relaxation in the routines, confidence in the construction, and finding yourself through the daily tending, tinkering, and touching.

As far back as 1843, in the book, The Ladies Work-Table Book, published in London by H.G. Clarke and Co, (unattributed because it was considered "unseemly" for women to author books,) it is written that “Needle Work, Knitting and Netting, occupy a distinguished place, and are capable of being made not only sources of personal gratification, but of high moral benefit, and the means of developing in surpassing lovliness and grace, some of the highest and noblest feelings of the soul.” We have come a long way from being relegated and confined to the parlour to engage in “woman’s work,” but “the noble feelings of the soul,” the spiritual and personal rewards we reap when we make something by hand, are timeless benefits. In fact, now more than ever, we need to be using our hands, our fingers, and our soul for something other than swiping a screen, clicking a mouse or pushing a button on a microwave.

What you do with these hands of yours does not have to be a grand opus or lofty pursuit. When people think of creating with their hands, their first thought goes to art and craft. That is all well and good, and it may already be your thing, but handwork is not exclusive to the arts. Think mending vs. needlework, polishing rather than sculpting, and digging instead of designing. Tuning an engine is handwork, as is trimming the shrubs or weeding the garden. The point is not busy work but to put your hands to purposeful work. You cannot find joy or meaningful work without your hands actively seeking it. As my mother often said, “How do you know you don’t like it if you haven’t tried it?” When I used the same line with my children, I wisely added the word lately, “Have you tried it lately,” because tastes and desires, likes and dislikes, change as we mature. Don’t let any fear, preconceived ideas, prior disinterest, dislike, or disappointments cloud your present.

No expectations. Give it a try. What have you got to lose? What would you make, what would you create if you knew you were going to lose the use of one or both of your hands tomorrow? Go do that now.

Quotes of the Week

When you really think about your hand you begin to realize its connection,

to sense the hum of your own being passing through it.

Emily Carr

We are all wearing our own handcuffs. We are also holding the key.

Marcie via Rachel Abel Schlessinger

as someone who broke their wrist and just recently fractured my elbow (3 months of recuperating) on my dominant hand, this is so relevant and I would echo "me, too" to your reactions. my wrist wasn't too bad during the recuperation (was able to do handwork and think it helped to get back to use more quickly) but the elbow was the worst in terms of getting back to being able to do stuff with that arm. one doesn't realize how much they use their elbows in their life.

the ironic aspect is that I was working on some beadwork, went to take my dog for a walk, and stepped up on the curb and face-planted. I then spent the next 3 hours in the emergency room-- there was no avoiding it. but after surgery, 6 weeks of a brace, and 6 weeks of therapy, somewhat back to my use. handwork has really helped oddly.

I appreciate being able to create again!!!

Everything you write makes me think.

The hands article in particular hits home.

My aunt ( age 90) had a stroke and lost the use of her left hand. The right one can barely hold a cup. As you so beautifully pointed out, we all need to stop and wonder at the power of our hands. Thank you for this moving article. Your words make a difference.